As the dust settles from Monday’s federal election, to paraphrase former prime minister Kim Campbell, it’s time to talk about serious issues again.

The Conservatives were hoping to make 2015 a free trade election, by signing onto the world’s largest trade deal at the end of July. But things didn’t go as planned at the talks in Maui, and Canada was among the players that walked away from the Trans-Pacific Partnership table at that time.

Then came five days of round-the-clock negotiations in Atlanta, with the U.S. pushing for a deal with Japan, Korea, Australia and other Pacific Rim powerhouses to normalize trade in 40 per cent of the world’s economy. And the TPP came together at the end of September.

Canada and B.C. essentially got what our governments were demanding, which was broad access to Pacific Rim markets and continued protection for nearly all of domestic dairy, poultry and egg markets. Also preserved was B.C.’s regulated market for logs and U.S. lumber sales.

The 200-kg gorilla of the TPP burst out in the heat of the election campaign, and the Kim Campbell rule was demonstrated again. Much of the discussion revolved around alleged secrecy, as the legal text of the deal won’t be out for some time to come. Protected farmers downed their pitchforks, counting their blessings, and their guaranteed compensation.

The NDP was forced to come out against the TPP, as it was against trade deals with the U.S., Mexico, Europe and others. But it’s getting lonely for them as the rest of the world moves on.

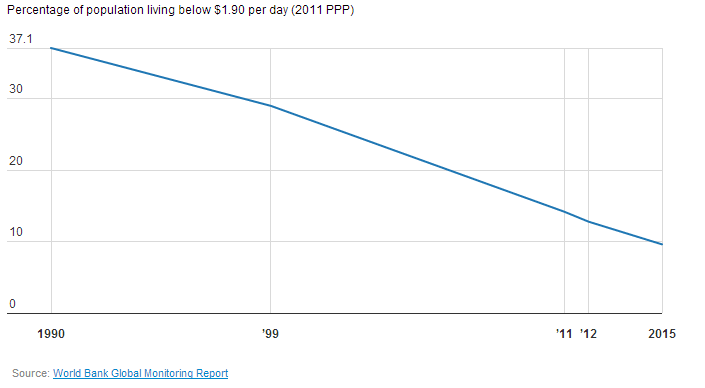

Within days of the TPP deal, the World Bank issued one of its periodic reports on “extreme poverty,” which it defines as an income of less than $1.90 U.S. a day. And 2015 is the first year when fewer than 10 per cent of the world’s people remain below this global poverty line, down from 12.8 per cent in 2012.

It’s easy for comfortable First World folks to protest conditions in running shoe and cell phone factories in India or China, but the graph of extreme poverty in those countries shows steep decline since 1990. Trade and technology are lifting up the poorest of the world.

For B.C., withdrawing from Pacific Rim trade is unthinkable. We worry a lot about lumber and copper and natural gas, but the TPP also opens up huge markets for services, where much of our economic future awaits.

The question for us is simple. Can we compete in health sciences, engineering, architecture, digital media, and information technology? Do we want to?

The TPP doesn’t change B.C.’s dependency on the United States. As with NAFTA, our vital lumber trade remains under a separate agreement, which expired on Oct. 12.

I’m told by federal and provincial officials that at this stage, the U.S. isn’t even taking our calls on the softwood lumber agreement, which Canada and B.C. want extended. Americans are preoccupied with the TPP and domestic politics.

After decades of bitter legal actions from the American industry, the latest softwood deal has provided a rough peace. It set a floor price for B.C.’s allegedly subsidized lumber exports, with an export tax collected by Canada when the price went below the floor of $355 per thousand board feet. That money went back into our government general revenue.

Higher prices meant no export tax was collected through 2014 and early 2015, and only five per cent as of September. Now that the agreement is expired, by default we have actual free trade in lumber for up to the next year.

Tom Fletcher is legislature reporter and columnist for Black Press. Twitter: @tomfletcherbc